Tibetans express concerns about accessing mother-tongue education

A recent change in higher admission score requirements in the eastern Tibetan province of Amdo, most of which is governed under the jurisdiction of Qinghai Province, is reigniting decades-long concerns about shrinking opportunities for Tibetans to pursue Tibetan-medium education. The shift signals a further step in the Chinese Communist Party’s assimilatory ethnic policy of eviscerating the Tibetan language – and therefore Tibetans’ identity.

Students at a school in Malho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture

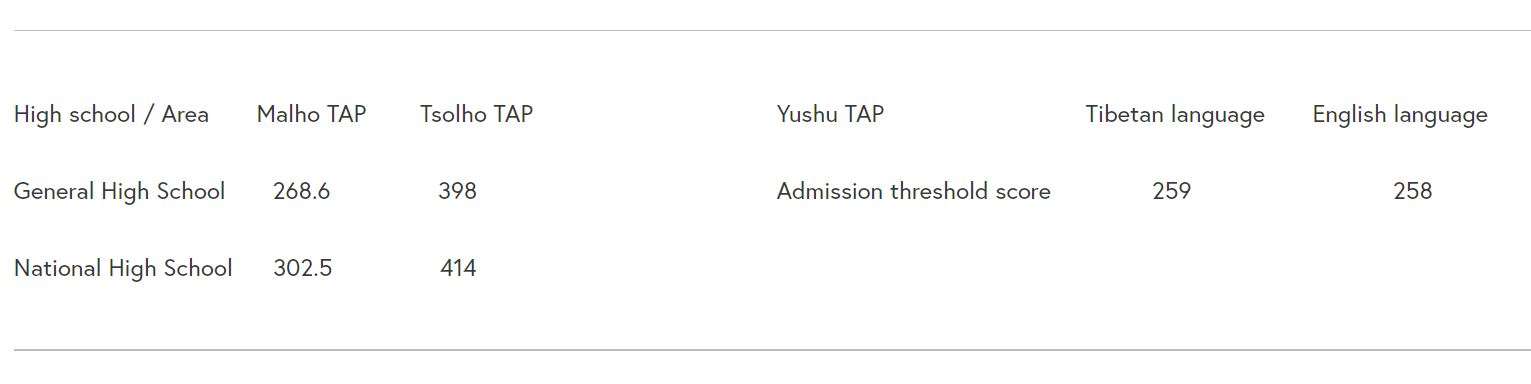

On 12, 13, 14 July 2021, The Ministry of Education in Tsolho, Malho and Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures issued notices, in Chinese, of higher admission score requirements for Tibetans enrolling in national high schools where Tibetan is the main medium of instruction. The previous test score threshold required for students to get admission to national high schools was increased and set nearly equal to general high schools where the main medium of instruction is Chinese.

This move is a serious setback for the Tibetan students aspiring to get admission to national high schools. It discourages them from enrolling in national high schools and restricts them to enrolling in general high schools.

Tibetans from the region have expressed their dismay on social media at this forced change. In a social media post, a Tibetan student who recently gave his entrance exam for national high school laments that there is no hope of getting admission. He further wrote,

“If I do not pass, it means no education in the Tibetan language. It will be too much to bear.. I love the Tibetan language.. I am beginning to consider returning to junior high school..”

Cultural assimilation through school and job-market

In addition to reduced access to Tibetan-medium education, “minority-nationality” graduates from national high schools face more difficulties in finding employment in the Chinese-language-dominated society and job market. More opportunities are available for those from general high schools with better competencies in Mandarin.

Without the recognition from the party-state of the importance of daily spoken and written Tibetan language, the local governments neither provide sustainable support for creating job prospects nor provide the freedom of school curriculum conducive for an environment of preservation and continuity of Tibetan identity.

The change stands in clear contradiction of Article 10 of Regional National Autonomy Law, which claims to support the use and development of local languages: “Autonomous agencies in ethnic autonomous areas guarantee the freedom of the nationalities in these areas to use and develop their own spoken and written languages and their freedom to preserve or reform their own folkways and customs.”

The report follows the forced closure of a private Tibetan school, Sengdruk Taktse, on 8 July, in Amdo, as well as many other similar private schools in the neighbouring province of Sichuan from the end of 2020, as reported by a source to Radio Free Asia.

The late 10th Panchen Lama (1938-1989) and innumerable dedicated Tibetan leaders have contributed immensely to the preservation and flourishing of the Tibetan language. After waves of protests in the build-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, and self-immolations from February 2009, the Qinghai authorities, from 2010 onwards, changed their previously relaxed approach to switch “minority-nationality’” schools to Chinese-medium teaching.

The culmination of these repressive policies and unaddressed grievances led to around 1000 high school students, including small children, in Rebkong (Ch.: Tongren), Malho to stage a protest in March 2012, calling for their language rights to be respected. Over 500 Tibetan students from Minzu University in Beijing also protested in solidarity and several hundred Tibetan teachers submitted a joint letter arguing for the importance and scientific basis of education in mother-tongue. A group of retired Tibetan officials, as well as scholars and poets, also critiqued the authorities despite the prevalence of a highly militarised atmosphere of fear and repression. The protests spread across Amdo.

Leaked documents from Tsolho Tibet Autonomous Prefecture revealed the authorities’ intentions of reforming the education system and caused hundreds of Tibetan netizens to voice their resistance in April 2017. In a social media post from Tibet, translated by High Peaks Pure Earth, one Tibetan netizen called Tsering Kyi wrote, “the transformation of the education system is not like gambling and it is also not like a guinea pig in an experiment, it will implicate the lives and fortunes of several generations”.

Similarly, on sensing the lack of legal protection for spoken and written Tibetan language, Tashi Wangchuk, a Tibetan nomad and shopkeeper from Kyegudo, Yushu Tibet Autonomous Prefecture, went to meet officials in Beijing to bring to their attention the absence of a real Tibetan education system in his hometown. After five years of imprisonment which reflected once again the CCP’s disregard for its own laws and Tibetan voices, he was released in January 2021 under heavy surveillance.

Sources reported to Tibet Watch that even at the university level in Tibet, the main medium of instruction is Mandarin and learning in Tibetan is confined only to “Tibetan studies”. For example, at Xizang Minzu University in central Tibet, all the other courses such as law, maths, geography and finance etc. are taught in Chinese despite the overwhelming majority of students being Tibetan. In a 2019 news report by Radio Free Asia, sources reported that “The Tibetan students specializing in Tibetan medicine are facing a lot of challenges and problems of comprehension because their subjects are now taught in Chinese.”

Rigney chu, Knowledge system in Tibet

Tibet’s knowledge system is one of the richest and oldest in Asia which has developed over centuries with a unique combination of precision and complexity. The vast field of knowledge, known in Tibetan as Rigney Chu,(རིག་གནས་བཅུ།) loosely translated as ten sciences, comprises:

རིག་གནས་ཆེ་བ་ལྔ་ནི། Five Major Sciences:

བཟོ་རིག་པ་དང་། Arts and Technology

གསོ་བ་རིག་པ། Sowa rigpa /Medicine and Wellbeing

སྒྲ་རིག་པ། Science of Grammar

ནང་པའི་གཏན་ཚིགས་རིག་པ། Epistemology/Logic

ནང་དོན་རིག་པ། Philosophy/Psychology

རིག་གནས་ཆུང་བ་ལྔ་ནི། Five Minor Sciences

སྙན་ངག་། Poetry

མངོན་བརྗོད། Lexicography

སྡེབ་སྦྱོར། Prosody

ཟློས་གར། Performing arts/Dramatical composition

སྐར་རྩིས། Astrology/Mathematics

These translations in English are a modest attempt to encapsulate the form and content of Rigney chu, the root classification of the knowledge system, from which emerges a multitude of branch knowledge. Not only is the subject-based knowledge classification system of Tibet one of the oldest in the world, but the Tibetan language also carries the inherent abilities for expressing and learning the multi-dimensions of knowledge. The assimilatory education policies, therefore, impede the depth and vastness of the Tibetan language from flourishing and stifle the expression and intellectual scholarship that Tibetan students and teachers are innately best capable of.

Note: Tibetan’s demand for freedom is also carried through translations in different languages by many Tibetan writers in many languages. In one example of Tibetan exiles’ advocacy on spoken and written Tibetan language and freedom of language, read here the late Lobsang Chokta’s important speech at the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee. Lobsang was vice president of PEN Tibetan Writers who passed away in a tragic incident at the age of 34 on 12 February 2015. In exile, writers and poets, Tibetan media outlets continue to gather and publish censored stories and histories from Tibet in Tibetan and English. Likewise, Tibetan schools and administrations in exile and institutes like Central Institute for Higher Studies were constructed during the ongoing occupation of Tibet with the mission to preserve the Tibetan language and identity.