Introduction

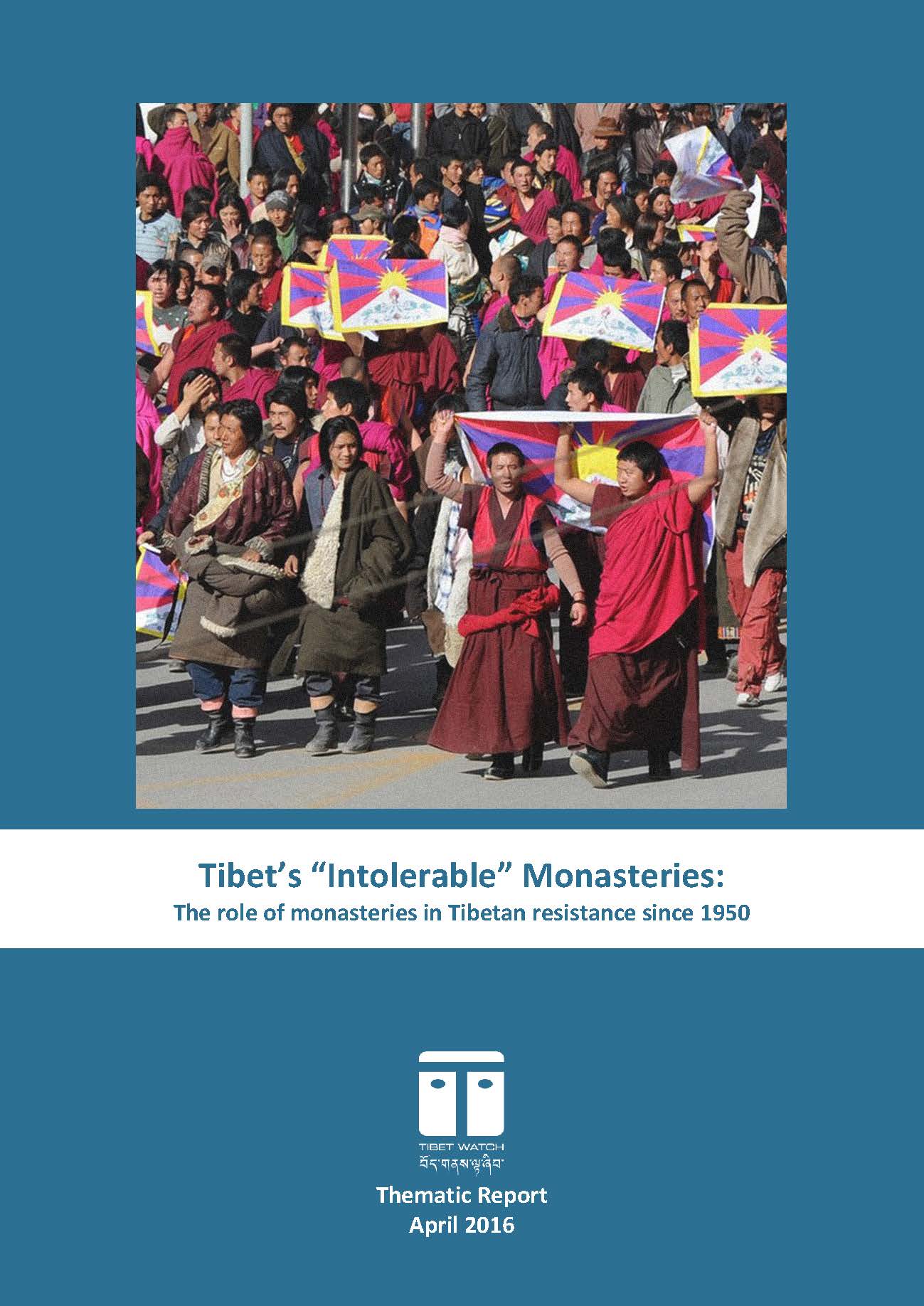

This report examines the role of Tibetan Buddhist institutions in Tibetan resistance. In particular, the report will focus on several monasteries and one nunnery spanning all three traditional provinces of Tibet (Amdo, Kham and U-Tsang) to provide an overview of the breadth of resistance activities.

Prior to the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, government was largely theocratic and religious institutions played a number of different roles. First and foremost, they were institutes of religious study and practice and developed influence based on the quality of their research and teaching in much the same way as prestigious universities. However, they also provided education for the lay communities that lived around them. They acted as financial institutes, offering loans but also investing in local agriculture, herding and other projects. They offered an arbitration service and resolved disputes between neighbours and families. Monks were strongly represented in the government and monasteries often acted as local political centres.

In the first few years of the occupation, very little changed. China trod carefully as it tried to induce the Dalai Lama to accept that Tibet was now an integral part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The peaceful approach did not last, however, and Mao soon embarked upon a process of appropriation which saw many monasteries and nunneries stripped of their land and much of their property. This triggered a period of protest and unrest, culminating in the uprising of 1959. The response was swift and violent. Monasteries were subjected to aerial bombing; people were killed, arrested, sent to labour camps.

Perceived as bastions of traditional values, religious institutions in Tibet were systematically attacked again during the Cultural Revolution. Even private religious observance became illegal. The repression lifted somewhat with the death of Mao and the Cultural Revolution. The new leader, Deng Xiaoping, initiated a gentler approach and religion regained its place in day-to-day life in Tibet.

However, as they watched the temples and monasteries being rebuilt, Tibetan people enthusiastically re-embracing religious practice, Chinese authorities started to articulate their concerns. The influence of Tibetan Buddhism was once again considered a threat to China’s control over Tibet…